|

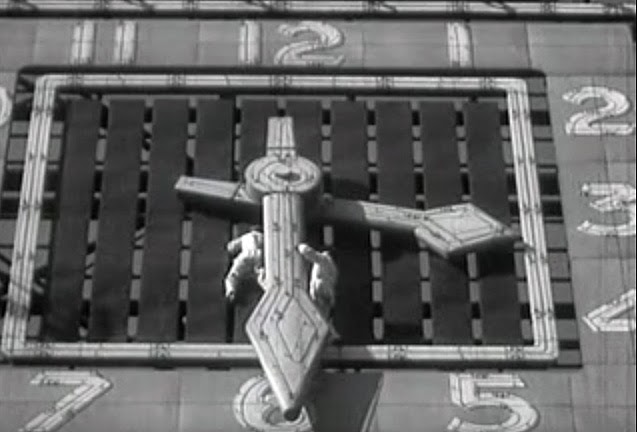

| Photograph: 1934, Gordon Coster, courtesy Calumet412 |

If the Donald Trump sign wasn't already nearing the endpoint of its 15 minutes of fame. my appearance

on a Tuesday panel on WTTW's Chicago Tonight with Ward Miller and Peter Exley, hosted by Elizabeth Brackett, discussing the topic should finish it off for good. And so, I thought it a good time to tell you about another, now-forgotten sign that makes Trump's look like chump change.

In the 1930's, a spectacular, 23-story-high sign hawking Chevrolet was erected near what was then the Illinois Central Railyards. on Randolph just east of Michigan. It's largely forgotten today, but Chevrolet commissioned a promotional film,

Behind the Bright Lights, a “Jim Handy picture” to document all the details behind the massive project.

The film tells how “sign monkeys” attended to the “millions of lights, and how the average bulb would have a life of 6 to 8 months. “Rarely a day passes within 30 to 40 having to be replaced.” According to the film, an electrical engineer was always on site. The lights were controlled by something called “a flasher”, whose 305 separate contacts made it “the largest one in the world.”

Another machine controlled the hands of the massive clock, “and it has kept the clock in perfect time for over a year without a slip.” (See? Donald Trump didn't invent hyperbole.)

The promotional film goes into fascinating detail about how the whole thing works. Actually, it's how all signs of this type - now largely only a memory - worked. Chevrolet just did it on a completely larger scale. The scrolling text was made possible by a moving “motograph.”

You want to know how it works? Well, every light bulb connects by a wire to a small contact point or brush. The tip of the brush presses against a copper plate, and the return wire carries electricity through the plate, brush and wire to light the lamp. A strip of paper inserted between the copper plate and the brush stops the flow of electricity and the lights go out. But where a hole in the paper lets the brush touch the copper plate, electricity flows through again and lights the bulb. No matter how many light bulbs and crushes are connected, each of them operates the same.

If a strip of paper is passed between the copper plate and the brushes, the lights will all go out. But wherever holes in the paper permit any brushes to touch the copper plate, the lights connected to these brushes will go on. The message is punched in a role of heavy paper, light a player piano roll. When the paper passes between the brushes and the copper plate, different groups of lights on the sign panel flash on and off and when running, makes you think the lights are moving, when they're not.

It apparently didn't take too many years for the sign to become more trouble and expense than it was worth, and by the 1940's it had been converted into a massive multichrome promotion for Pabst Blue Ribbon.

|

| photograph Jack Delano, courtesy Library of Congress |

And then the sign was torn down. By 1952, the corner had been taken over by a rather inelegant construction promoting Coca-Cola and Four Roses Whiskey, the Skid Row staple.

And then that sign disappeared as well, and in its place rose a new construction, the audacious

Prudential Building, the first new Chicago skyscraper since the Great Depression. Beginning in the 1970's, the massive railyards atrophied and were covered over by the sleek towers of Illinois Center. Across the street?

Millennium Park, this summer celebrating the 10th anniversary of its opening. There's a sedate sign atop the Prudential, but today the most prominent branding is expressed not in text, but in the billowing sales of Frank Gehry's

Pritzker Pavilion.

0 comments :

Post a Comment