|

| photograph: Bob Johnson (click images for larger view) |

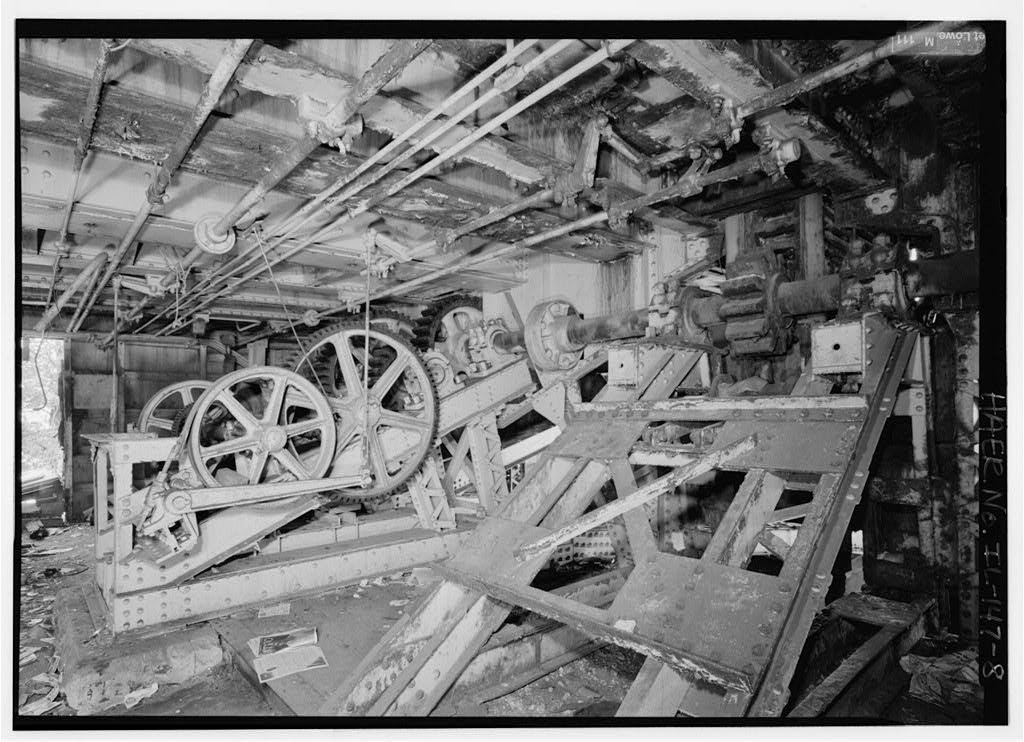

Constructed in 1903, the East Division Street Bridge over the North Branch Canal at Goose Island was the direct result of the investigations of Chicago City Engineer John Ericson to find an alternative to the city's traditional swing bridges, whose center piers had become navigational hazards as commercial traffic on the river intensified. Inspired by London's Tower Bridge of 1894, Ericson and his team came up with what became known as the double-leaf bascule, with two movable segments raised and lowered by motorized equipment at each bank, leaving the center of the waterway unobstructed.

|

| photograph: Library of Congress |

|

| photograph:Bob Johnson |

|

| photograph: Library of Congress |

For much of its life, the area around the bridge was home to coal and lumber yards, and during World War II the bridge again proved its worth as river traffic boomed. After the war, however, shipping entered a steep decline. The coal and lumber yards closed down, leaving vacant land. By the 1970's, the city called for closing many bascule bridges that were seldom lifted and expensive to maintain. The East Division Street bridge rose for the last time in the 1990's. $6 million has been budgeted to demolish the bridge and replace it with a “temporary” span.

I was at the bridge on the morning of May 16, 1992, when legendary Chicago author Studs Terkel was joined by Mayor Richard M. Daley, Mike Royko and others in dedicating the bridge to the author whose landmark book, Division Street: America chronicled the thoroughfare as a microcosm of Chicago history. The bridge was re-dedicated in 2012, in what would have been Terkel's 100th year, and there's already a move afoot to make sure the replacement bridge also bears his name.

No one ever mistook the East Division Bridge for a romantic construction, but there was a surprising bit of ornament. Along the steel of the bridge's overhead bracing, there were repeating punches of the Chicago “Municipal Device”, the Y-shaped civic symbol that represents the merging of the three branches of the Chicago River at Wolf Point. Their use on the structure can be seen in Urban Remains Eric J. Nordstrom's documentation on the destruction of the bridge here, here, and here.

As has been a constant since the 19th century, funds for maintaining the city's infrastructure were often been sparse, and time had not treated the East Division Street Bridge kindly, with major renovations widely spaced in the early 30's, 1969, and then again in the 1980's. Recently, it's members had been painted pink. In April of this year, trucks and buses were prohibited, and on June 30th, the bridge closed to traffic for the last time.

As can be seen at the photograph at the top of this post from our indefatigable correspondent Bob Johnson, the wreckers made quick work of it. By the time I got there it little more than a week ago, the imposing metal structure that had dominated the view down the channel for 117 years had completely vanished. You could almost imagine it had never existed, if it weren't for those giant concrete moorings on either bank, standing like some mysterious ancient ruin whose meaning still awaited deciphering.

0 comments :

Post a Comment